φίλοι

philoi, friends, confidants, dear ones

philoi, S 5384; TDNT 9.146–171; EDNT 3.427–428; NIDNTT 2.547–551; MM 671; L&N 34.11; BDF §§190(1), 227(2); BAGD 861

When the Lord calls his apostles “friends,” he bases this choice of words on the fact that “I have made known to you all that I heard from my Father.”1 We can refer to the disciplina arcani, so important in the rabbis and at Qumran,2 but we should also recall a specific meaning of philos, namely, “confidant, one to whom a secret is entrusted,” not only because “all things are common to friends,”3 and not only because the master-disciple relationship is assimilated to a friendship relationship,4 but because people entrust their most intimate and precious secrets only to those whom they love and in whom they have confidence.5 Cf. Philo, Dreams 1.191: “The word of God addresses some as a king authoritatively telling them what to do.… For others, it is a friend who with persuasive gentleness reveals numerous secrets that no profane ear may hear.” It is in V 3, p 449 this sense that “the prophet is called the friend of God” (Moses 1.156), especially Moses, to whom God spoke with the confidence and intimacy that people use with friends (hōs pros ton heautou philon, Exod 33:11). “The wise are friends of God, especially the most holy lawgiver. For freedom in speech is akin to friendship: with whom does a person speak freely, if not with a friend? Thus it is altogether fitting that Moses should be celebrated in the Scriptures as the friend; thus all that he risks saying in his boldness can be chalked up to friendship.”6

St. Paul bids Titus, “Greet those who love us in the faith” (aspasai tous philountas hēmas en pistei, Titus 3:15; cf. P.Yale 80, 11; 83, 24; P.Mich. 477, 3), and St. John says to the elder Gaius, “The friends greet you. Greet the friends by name” (aspazontai se hoi philoi, aspazou tous philous kat’ onoma, 3 John 15).

Both expressions recur often in the epistolary papyri: aspazou tous philountas hymas (P.Lund 3, 17; cf. P.Ryl. 235, 5); aspasai tous philountas se pantas (P.Oxy. 1676, 38–39; cf. BGU 332, 7); aspazou tous philountes pantes pros alētheian.7 Greetings are sent to a father, mother, sister, all those in the household, and friends: aspazome Ammōnan ton patera mou kai tēn mēteran mou ka tēn adelphēn kai tous en oikō pantas kai tous philous (P.Mert. 28, 17); “Greet my mother, my sisters, the children, and all who love me” (tēn mēteran, tas adelphas, ta paideia, pantas tous philountas me aspazou, Pap.Lugd. Bat. XVII, 16 b 19; cf. P.Oxy. 2594, 15). These “friends” could be friends in the strict sense8 or it could mean mere acquaintances: “Greet Theon and Zoïlus and Harpokras and Dionysus and all of our people.”9 Similarly the V 3, p 450 “friend and benefactor” of a city (TAM III, 139), or “friend and ally” (1 Macc 10:16; 12:14; 15:17, and the inscriptions—I.Magn. 38, 52; SEG XIX, 468, 32; XXIII, 547, 2, etc.); even the passerby (addressed by an epitaph, TAM III, 548).

So it is often necessary, and a sign of profound affection, to greet each one “by name”: “I greet my very sweet daughter Makkaria … and all of our people by name” (aspazomai tēn glykytatēn mou thygatera Makkarian … kai holous tous hēmōn kat’ onoma, P.Oxy. 123, 21–23; cf. 930, 22–26); “Greet all of your people warmly by name”;10 “Greet all those who love us by name” (aspazou pantas tous philountas hēmas kat’ onoma, P.Athen. 62, 30, first-second century; cf. P.Oslo 151, 20; P.Warr. 18, 30); “Greet Tasokmenis my esteemed sister and Samba and Soueris and her children and Sambous and all the relatives and friends by name” (aspazou Tasokmēnin tēn kyrian mou adelphēn kai Samban kai Souērin kai ta tekna autēs kai Samboun kai pantes tous syngeneis kai philous kat’ onoma, P.Mich. 203, 34); “I greet my daughter warmly and your mother and those who love us by name.”11 These parallels to 3 John 15 are quite numerous, but the best of them all is this, from a second-century ostracon: Annius, writing to his “very sweet friend” (glykytatō), concludes, “The friends greet you. Greet … the guardian and Niger … and all by name.”12

In the epitaphs, the adjective philos is used especially with father, mother, child, parents;13 in the papyri, it is especially the superlative philtatos that is used, notably in greetings. In AD 1: “Dionysius to Theon, tō philtatō pleista chairein” (P.Oslo 47, 1; cf. 49, 1; 56, 1; 82, 6; 85, 8); in 58, the V 3, p 451 same expression, from Chairas to Dionysius (P.Mert. 12, 1; cf. 23, 1; P.Mich. 210, 2; 503, 1); in 68, Heracleides greets his very dear Satabous.14 Christians take up the apostolic formulas15 and can be very expressive of their affection: “It is the same toward you, dearest one, for as in a mirror you see my engrafted affection and love for you, which is always fresh” (to auto de estin kai pros se, ō philtate, kai gar hōs di esoptrou katides tēn pros se mou emphyton storgēn kai agapēn tēn aei nean, P.Oxy. 2603, 17).

V 3, p 452 Φιλόλογος

Philologos, Philologus

Philologos, S 5378; EDNT 3.427; NIDNTT 2.550; MM 670; L&N 93.380; BAGD 860

As a common noun, this word does not occur in the Bible. It can have a positive or a pejorative sense: “one who loves to talk, a babbler” or “one who loves literature, a scholar” (Epictetus 2.4.1; 3.10.10; 4.22.107; TAM 2.919: ton agathon philologon). It is applied especially to the Athenians.1 It is used in official praise (MAMA VIII, 263), for example, for physicians (TAM II, 147, 5; CIL III, 614; cf. V. Nutton, “Menecrates of Sosandra, Doctor or Vet?” in ZPE, vol. 22, 1976, p. 96), and epitaphs and letters apply it to students,2 even to a young girl: Tetria, philologe, chaire (SEG, XXII, 335, 1–2).

V 3, p 453 The proper name Philologus, mentioned in Rom 16:15, is fairly common at Rome in the familia of Caesar’s household (CIL VI, 4116), in Egypt,3 and in Asia Minor.4 It seems to be particularly common for slaves and freed slaves;5 as in this inscription: “Philologus, chief huntsman, for faithfulness and hard work.”6 The absence of a patronymic, the tasks that are entrusted to him, and the qualities that he has demonstrated indicate an inferior social standing.

V 3, p 454 φιλοξενία, φιλόξενος

philoxenia, hospitality; philoxenos, hospitable

→see also ξενία, ξενίζω, ξενοδοχέω, ξένος

philoxenia, S 5381; TDNT 5.1–36; EDNT 3.427; NIDNTT 1.686, 690, 2.547, 550; MM 671; L&N 34.57; BAGD 860 | philoxenos, S 5382; TDNT 5.1–36; EDNT 3.427; NIDNTT 1.686, 690, 2.550; MM 671; L&N 34.58; BAGD 860

Christ mentioned hospitality as a distinguishing characteristic of his true disciples,1 and in the primitive church it was the most obvious and most common work of love, shown either to journeying brethren (cf. Jas 4:13) or especially to preachers of the gospel.2

V 3, p 455 Among the works of brotherly love,3 Rom 12:13 commends eagerness to welcome traveling Christians: “pursuing hospitality” (tēn philoxenian diōkontes). We may compare b. Šabb. 104a (“Such is the custom of the merciful [Hebrew ḥasidîm] of pursuing the poor”) or Gallias, a citizen of Agrigentum in the fourth century BC, who received numerous xenōnes in his house. He was so philanthrōpos and philoxenos that he posted his slaves at the city gates to welcome strangers when they presented themselves and ask them to his house.4

In the Hellenistic period, philoxenia is an act of philanthrōpia;5 the stranger, received as a guest, is addressed and treated as a friend (xenos kai philos),6 and the Greeks honor those who practice broad hospitality. At Chersonesus, a benefactor of the city is praised because in time of famine he personally showed hospitality to citizens of the city (idioxenoi, B. Latyschev, Inscriptiones Antiquae, IV, n. 68, 15). Sotis and Theodosius receive praise “for the good offices toward travelers going from Athens to the Bosporus” (Dittenberger, Syl. 206, 50–51); likewise Aglaos of Cos, “who always honors and gives a noble welcome to those who come to him from our various cities either as envoys or for some other reason … working to do good to each of those who ask him.”7 In AD 43, Junia Theodora, a Roman living at Corinth, is honored by a decree by the Lycian confederation and the deme of Telmessos because she “tirelessly showed zeal V 3, p 456 and generosity toward the Lycian nation and was kind to all travelers, private individuals as well as ambassadors, sent by the nation or the various cities.”8

Spanish hospitality was imbued with a religious spirit.9 Semitic hospitality was particularly generous, as is suggested by T. Job 10: “I also had thirty tables put in my house, which were at all times kept ready only for strangers.… And if a stranger asked for alms, he had to take a meal at table before receiving what he needed. I did not allow anyone to leave my home with an empty stomach.” This hospitality of Job is referred to in ʾAbot R. Nat. 7.1–3 (cf. Str-B, vol. 4, 1, pp. 566–567).

In the Christian church, it was the bishop, acting as host on behalf of the local community, who was philoxenos and offered a bed and shelter to traveling brothers (1 Tim 3:2; Titus 1:8). But for all Christians, hospitality was to be the first evidence of their philadelphia, according to Heb 13:2—“Do not neglect hospitality (tēs philoxenias mē epilanthanesthe), for through hospitality some have without knowing it entertained angels.” The stranger who is welcomed is a messenger of God. This religious motivation refers first of all to Abraham,10 but also to Lot (Gen 19), Manoah (Judg 13:3–22), and Tobias (Tob 12:1–20).

These examples make an impression, as does the promised reward,11 which was important, because hospitality was onerous. Everything that the travelers needed had to be supplied,12 and certain people abused their V 3, p 457 host’s goodness (Did. 11.3–6; Herm. Man. 2.5). Consequently, many people tried to keep their doors closed.13 Hence the added detail in 1 Pet 4:9—“Practice hospitality to one another without grumbling” (aneu gongysmou).

Philoxenos is unknown in the papyri,14 and the noun is attested only in a Christian letter from the fourth century: “I write this letter on this papyrus so that you may read it with joy … and with a welcoming attitude borne of patience, filled with the Holy Spirit.”15

V 3, p 458 φίλος τοῦ Καίσαρος

philos tou Kaisaros, king’s friend

philos tou Kaisaros, S 5384 + 2541; EDNT 2.235; BAGD 395–396

The title of honor “king’s friend,” used at the Persian, Egyptian, Lagid, and Seleucid courts,1 then at Rome,2 ordinarily refers to high dignitaries who dress in purple,3 have free access to the king, serve as councillors,4 V 3, p 459 and are entrusted with civil and military functions (1 Macc 11:26; 2 Macc 1:14; 10:13; 14:11). The seventeenth book of Diodorus Siculus supplies a great deal of data on the “friends” or “companions” of Alexander and of Darius (cf. F. Carrata Thomes, “Il problema degli eteri nella monarchia di Alessandra Magno,” in Università di Torino, Pubbl. della Fac. di Lett. e Fil., vol. 7, 1955, pp. 14–15, 27ff.). The king assembled his “friends” in council (17.16.1; 16.30.1) and asked for their honest opinions (17.39.2; 17.54.3). Some shared his own opinion (17.45.7); others said the opposite (17.30.4). They gave the king information (17.112.3; 17.115.6) and inquired concerning his intentions (17.117.4). There was a hierarchy among these principal collaborators (17.107.6; 17.117.4), who were chosen from among the most capable men (17.31.1), esteemed by the king (17.37.5), beloved (17.114.1), and enjoying his confidence (17.32.1). He feasted with them (17.16.4; 17.72.1; 17.73.7; 17.100.1; 17.110.7; 17.117.1) because they went with him when he moved from place to place (17.96.1; 17.97.1; 17.104.1; 17.116.5); and he entrusted delicate assignments to them (17.37.3; 17.52.7; 17.55.1; 17.104.3; 17.112.4). He distributed honors and wealth to them (1.35.2; 17.77.5; cf. Athenaeus 12.539 f). These friends sought the king’s good and were ready to stand with him in danger (17.56.2; 17.97.2; 17.117.2), but sometimes they were obsequious (17.115.1; cf. 17.118.1) and jealous of each other (17.101.3), and sometimes they went so far as to plot together against the king (17.79.1; 17.80.1). According to Polybius, King Philip of Macedonia took counsel with his friends (5.2.1; 5.4.13; 5.22.8). He gathered them for deliberations (5.58.2; 5.102.2). They shared the same convictions (5.9.6) and were similarly influenced (5.36.8), but they could be circumvented by intriguers (5.50.9). The friends voted unanimously (5.16.7) and the king’s decision followed their opinion (5.63.3). They accompanied the king (5.56.8–9; 5.87.6; 5.101.5), surrounded and assisted him (5.12.5), and shared in his responsibilities (5.16.5), especially the command of his troops (5.21.1; 5.83.1).

Among the “friends of the king” three or four levels of hierarchy can be distinguished: mere friends,5 honored friends,6 first friends,7 and finally V 3, p 460 the syngenēs or “king’s kinsman”;8 but this title was also granted to vassals, and was no more than an honor, a distinction (1 Macc 2:18; 11:57; 15:32; SEG VIII, 573; Philo, Flacc. 40; P.Oxy. 3022, 12), and “first friends” could be on the same level as the chiliarchs and machairophoroi of the royal guard.9

When the Jews cry out to Pilate, regarding Jesus, “if you release him, you are not a friend of Caesar (ouk ei philos tou Kaisaros), for whoever makes himself a king is against Caesar,”10 there are three possible interpretations: (1) a commonplace appeal to loyalty, a litotes meaning, “You would be an enemy of Caesar not to condemn this royal pretender”;11 (2) the technical meaning amicus Augusti;12 (3) but Pilate is not a dignitary or important and influential person at the imperial court.13 The final option is that this V 3, p 461 distinction is conferred upon him as an equestrian14 and governor of Judea, but with the fluidity of meaning that marked this official “friendship” in this period.15

The thought of incurring the emperor’s disfavor won out over Pilate’s belief in Jesus’ innocence (ouden heuriskō aition, Luke 23:4, 14). Losing the emperor’s favor would mean the end of his career, or at least a compromised future, the ruin of his ambitions, perhaps the confiscation of his wealth, loss of liberty, perhaps even exile or death.16 Pilate gave in to the blackmail.

V 3, p 462 φιλόστοργος

philostorgos, authentically loving, tenderly devoted, beneficent

philostorgos, S 5387; EDNT 3.428; NIDNTT 2.538–539, 542, 550; MM 671–672; L&N 25.41; BAGD 861; ND 2.101–103, 3.41–42

The first characteristic of “authentic love” (Rom 12:9) is that it fills Christians with tender devotion to each other (verse 10; cf. F. Cumont, Studia Pontica III, 20, 14). Thus may we translate philostorgoi, which in the Koine often replaces the simple form storgē,1 which expresses familial affection, an attachment sealed by nature and blood ties, uniting spouses, parents and children, brothers and sisters.2 Because this instinct or feeling is shared by animals and humans,3 Philo considers it a virtue only to the extent that it remains under the rule of reason;4 but in common usage, usage philostorgia has the more positive sense of the mother’s innate love, V 3, p 463 benevolence, and devotion toward her children;5 then that of a husband for his wife6 or a wife for her husband;7 of a father for his sons8 and of V 3, p 464 sons for a father.9 But philostorgia is also used for all links of kinship,10 even one’s attachment to guest-friends (SEG XVIII, 143, 69), or the attachment of slaves to their master.11

Quite often, philostorgia is identified with gratitude.12 Not only do writers of wills leave their property to those who have shown affection for them,13 but on August 29, 58, Phairas writes to his physician: “I hope that if I cannot return in equal measure the affection you have shown me, I may at least show some token of gratitude.”14 This extension of philostorgia to strangers shows that this sentiment is not limited to mere benevolence15 but also includes active beneficence, devotion, and generosity; thus Hippolytus appeals to the dioikētēs Acusilaus: “I beseech you, in your philostorgia, concerning my sons who are with Soterichon …”16

In the language of the inscriptions from the second century BC, philostorgos is synonymous with “benefactor.” A decree of Athens confers praise and a gold crown to King Attalus I as the benefactor of the city “with all goodwill and philostorgia.”17 Attalus II honors his brother Eumenes II “for V 3, p 465 virtue and goodwill and his philostorgia toward him” (aretēs heneken kai eunoias kai philostorgias tēs pros heauton, I.Ilium, n. 41). Attalus III writes “so that you may know how much philostorgia we have for him.”18 The merchants of Laodicea erect a statue in honor of Heliodorus “because of his goodwill and philostorgia toward the king and good deeds toward themselves” (eunoias heneken kai philostorgias tēs eis ton basilea kai euergesias tēs eis hautous, Dittenberger, Or. 247, 6). The city of Gythion honors the public physician Damiadas “who has in everything abundantly demonstrated his goodwill and philostorgia toward our city.”19 The word is also used for devotion to country20 and with a religious meaning as an epithet for the savior goddess Isis of Carene;21 but with the abuse of the expression, especially in the honorific inscriptions,22 it came to be purely a polite term and an expression of official “sympathy” (2 Macc 9:21; cf. Dittenberger, Or. 257, 4; TAM II, 283, 360, 443, 484, 662, 716, etc.) or of some undifferentiated form of attachment.23

S J. Strong. Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Reprint. Peabody, n.d.

TDNT G. Kittel and G. Friedrich, eds. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. Trans. G. W. Bromiley. 10 vols. Grand Rapids, 1964–1976.

EDNT H. Balz and G. Schneider, eds. Exegetical Dictionary of the New Testament. Grand Rapids, 1990–1993.

NIDNTT Colin Brown, ed. The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology. Grand Rapids, 1986.

MM J. H. Moulton and G. Milligan. The Vocabulary of the Greek Testament Illustrated from the Papyri and Other Non-literary Sources. 2 vols. London, 1914–30. Reprint. Grand Rapids, 1985.

L&N J. P. Louw and E. A. Nida, eds. Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament: Based on Semantic Domains. 2 d ed. New York, 1989.

BDF F. Blass and A. Debrunner. A Greek Grammar of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. Trans. and rev. of the 9 th–10th German edition incorporating supplementary notes of A. Debrunner by R. W. Funk. Chicago, 1961.

BAGD W. Bauer. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. 2 d ed. Trans. W. F. Arndt and F. W. Gingrich. Revised and edited F. W. Danker. Chicago, 1979.

1 John 15:15 (cf. Luke 12:2–4). Cf. W. Grundmann, “Das Wort von Jesu Freunden (Joh. XV, 13–16) und das Herrenmahl,” in NovT, 1959, pp. 62–69; G. M. Lee, “John XV, 14: ‘Ye Are My Friends,’ ” ibid. 1973, p. 260; E. A. Judge, The Social Pattern of Christian Groups in the First Century, p. 38.

2 J. Jeremias, Eucharistic Words, pp. 76ff.; C. Spicq, Agapè, vol. 3, p. 165, n. 5.

3 Κοινὰ τὰ τῶν φίλων, a Pythagorean maxim that was often quoted, Plato, Lysis 207 c; Phdr. 270 e; Resp. 5.462 c; Aristotle, Pol. 2.2.1263a29–30; Eth. Nic. 8.11.1159b31; Euripides, Or. 735; Plutarch, Amat. 21.9; De adul. et am. 24; Athenaeus 1.14.8 a. On the mediation of friends, cf. A. Biscardi, “Μεταξὺ φίλων, clausola di stile nei documenti di manomissione dell’ Egitto romano,” in Studi in on. di E. Volterra, vol. 3, Milan, 1971, pp. 515–526.

4 Aristotle, frag. 673 R; P.Hercul. 1018, col. XII, 5; H. I. Marrou, Histoire de l’éducation, p. 62 = ET, pp. 57ff.; C. Spicq, Agapè: Prolégomènes, pp. 26ff., 181ff.

5 St. John Chrysostom comments thus: “As the greatest proof of friendship is to entrust secrets (τὰ ἀπόρρητα), he tells them that he has deemed them worthy of such a communication (τῆς κοινωνίας).”

Dreams On Dreams (De Somniis)

Moses On the Life of Moses (De Vita Mosis)

6 Philo, Heir 21; cf. Plato, Tim. 53 d: “As for the higher principles, they are known only to God, and among mortals only to those who are friends of God”; Aeschylus, Pers. 160, 169: “It is to you that I wish to say everything, friends … advise me”; Thales: “One must believe one’s friends even when they say the unbelievable” (in Plutarch, Conv. sept. sap. 17); Seneca, Ben. 6.34.5: “It is in a court, not in an atrium, that one looks for a friend; there he must be received, there kept; it is in our thought that he must find a secret sanctuary”; Ep. 3.2.3.

P.Yale Yale Papyri in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. 2 vols. 1967–1985.

P.Mich. Michigan Papyri. 15 vols. 1931–1982.

P.Lund Aus der Papyrussammlung der Universitatsbibliothek in Lund. 6 parts. Lund, 1934–1952.

P.Ryl. Catalogue of the Greek Papyri in the John Rylands Library. 4 vols. Manchester, 1911–1952.

P.Oxy. The Oxyrhynchus Papyri. 51 vols. London, 1898–1984.

BGU Aegyptische Urkunden aus den Koniglichen (later Staatlichen) Museen zu Berlin, Griechische Urkunden. 15 vols. Berlin, 1895–1983.

7 P.Fay. 118, 25; 119, 25; BGU 625, 35; P.Brem. 61, 42; P.Mich. 490, 18; 494, 15–16; 495, 32; cf. F. X. J. Exler, The Form of the Ancient Greek Letter: A Study in Greek Epistolography, Washington, 1923, pp. 114–115; C. Spicq, Agapè, vol. 3, pp. 85ff.; T. Y. Mullins, “Greeting as a New Testament Form,” in JBL, 1968, pp. 418–426; M. Landfester, “Philos.”

P.Mert. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Greek Papyri in the Collection of Wilfred Merton. 3 vols. 1948–1967.

Pap.Lugd. Bat. Papyrologica Lugduno-Batava. 24 vols. Leiden, 1941–1983.

P.Oxy. The Oxyrhynchus Papyri. 51 vols. London, 1898–1984.

8 P.Oslo 49, 11: ἀσπάζου τοὺς σοὺς πάντας καὶ τὸν κύριον Ἀπολλώνιον τὸν μόνον φίλον; C.P.Herm. 12, 14: οἱ φίλοι καὶ γνώριμοι; 1, 6: ἀναγκαῖος φίλος (cf. BGU 1874, 4; P.Oslo 60, 5; P.Mil.Vogl. 59, 13), γνήσιος φίλος (P.Fouad 54, 34; P.Oxy. 1841, 6; 1845, 6; 1860, 16); τῷ ἀγαθωτάτου σου φίλῳ (P.Mich. 498, 9).

9 Ἄσπασαι Θέωνα καὶ Θωίλον καὶ Ἁρποκρᾶν καὶ Διονυσοῦν καὶ τοὺς ἡμῶν πάντας, ed. E. G. Turner, “My Lord Apis,” in RechPap, vol. 2, 1962, p. 118, line 15 and 20.

TAM Tituli Asiae Minoris. Vienna, 1901-.

I.Magn. Die Inschriften von Magnesia am Maander. Ed. O. Kern. Berlin, 1900.

SEG Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum. Alphen, 1923-.

TAM Tituli Asiae Minoris. Vienna, 1901-.

P.Oxy. The Oxyrhynchus Papyri. 51 vols. London, 1898–1984.

10 Ἄσπασε πολλὰ τοὺς ὑμῶν πάντας κατʼ ὄνομα, P.Oxy. 2275, 16–17; cf. 2276, 28; PSI 838, 11; 1054, 10; 1332, 27; 1333, 24; 1423, 27.

P.Athen. Papyri Societatis Archaeologicae Atheniensis. Ed. G. A. Petropoulos. Athens, 1939.

P.Oslo Papyri Osloenses. Ed. S. Eitrem and L. Amundsen. 3 vols. Oslo, 1925–1936.

P.Warr. The Warren Papyri. Ed. M. David, B. A. van Groningen, and J. C. van Oven. Leiden, 1941. (= Pap.Lugd.Bat. I)

P.Mich. Michigan Papyri. 15 vols. 1931–1982.

11 Ἀσπάζομαι τὴν θυγατέραν μου πολλὰ καὶ τὴν μητέραν σου καὶ τοὺς φιλοῦντας ἡμᾶς κατʼ ὄνομα, P.Mich. 216, 26; cf. 209, 25; 221, 19: ἀσπάζομαι σε μετὰ τῶν τέκνῶν σου· ἀσπάζομαι καὶ τοὺς φιλοῦντας ἡμᾶς κατʼ ὄνομα; 476, 31; 477, 40–44; 479, 20; 491, 19; 493, 21; P.Harr. 104, 15; BGU 27, 15; P.Mert. 82, 16–19; P.Abinn. 6, 23–24; 25, 15; P.Ross.Georg. III, 4, 25–28; SB 7353, 19; 7336, 32–25; 7357, 20–23; 800, 33; P.IFAO II, n. 40, 11: ἄσπαζε τοὺς φιλοῦντας ἡμᾶς πάντας καθʼ ὄνομα; A. Bernand, Philae, I, n. 65: “X performed this act of adoration for his friends, by name, and for all their children, for the good”; P. Perdrizet, G. Lefèbvre, Les Graffites grecs du Memnonion d’Abydos, Nancy-Paris, 1919, n. 481, 492, 580.

12 J. Schwartz, “Deux ostraca de la région du wādi Hammāmāt” (in ChrEg, 1956, pp. 118–123; cf. O.Aberd. 70, 8). The schoolboy Arion prays each day for his father, and concludes ἀσπάζω πολλὰ τοὺς ἡμῶν πάντας κατʼ ὄνομα σὺν τοῖς φιλοῦντι ἡμᾶς (in Sel.Pap. 133, 21).

13 GVI: father (n. 1204, 1737, 2026), mother (1208, 1210, 1909), child (1206, 1350, 1389, 1849, 1923), parents (1361), friends in the strict sense (1211, 1; 1212, 1270, 1363, 1630; 1633, 1821); cf. Diodorus Siculus, “Le Lexique de l’amour dans les papyrus et dans quelques inscriptions de l’époque hellénistique,” in Mnemosyne, 1955, pp. 27ff.

P.Oslo Papyri Osloenses. Ed. S. Eitrem and L. Amundsen. 3 vols. Oslo, 1925–1936.

P.Mert. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Greek Papyri in the Collection of Wilfred Merton. 3 vols. 1948–1967.

P.Mich. Michigan Papyri. 15 vols. 1931–1982.

14 P.Berl.Zill. 9, 1; C.P.Herm. 1, 2 (first century); P.Corn. 51, 1; P.Princ. 163, 1; 187, 5; P.Rein. 112, 2; P.Mert. 83, 1; 90, 5; P.Mich. 602, 2; 634, 4; P.Yale 79, 3; 80, 13; 81, 2; 83, 2; 84, 2; P.Oxy. 3030, 2; 3063, 1; 3085, 1; 3086, 1; P.Mil.Vogl. 51, 2; 62, 2; 76, 2; 201, 2; P.Bon. 44, 1; P.Brem. 51, 1; 52, 1; Pap.Lugd.Bat. VI, 43, 4; XIII, 19, 1; in the plural, φιλτάτοις φίλοις (BGU 1568, 3, 17; P.Panop.Beatty 1, 244; P.Brem. 3, 4; P.Oxy. 2183, 3; 3026, col. I, 16; P.Mert. 66, 2; Pap.Lugd.Bat. XVII, 7, 1). The vocative φίλτατε is found especially in wishes: ἔρρωσο, φίλτατε! (P.Oslo 82, 13; P.Oxy. 2610, 11; 3030, 16; 3063,24; P.Yale 79, 29; 84, 10; P.Mert. 28, 22; P.Princ. 68, 15); γράφω σοι φίλτατε (Pap.Lugd.Bat. VI, 42, 29; 43, 9, 14).

15 M. Naldini, Il Cristianesimo in Egitto (cf. the index on ὄνομα, p. 409); J. O’Callaghan, Cartas cristianas griegas del siglo V, Barcelona, 1963, n. IV, 15–16; IX, 19; XXIII, 5; XLVIII.

P.Oxy. The Oxyrhynchus Papyri. 51 vols. London, 1898–1984.

S J. Strong. Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Reprint. Peabody, n.d.

EDNT H. Balz and G. Schneider, eds. Exegetical Dictionary of the New Testament. Grand Rapids, 1990–1993.

NIDNTT Colin Brown, ed. The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology. Grand Rapids, 1986.

MM J. H. Moulton and G. Milligan. The Vocabulary of the Greek Testament Illustrated from the Papyri and Other Non-literary Sources. 2 vols. London, 1914–30. Reprint. Grand Rapids, 1985.

L&N J. P. Louw and E. A. Nida, eds. Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament: Based on Semantic Domains. 2 d ed. New York, 1989.

BAGD W. Bauer. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. 2 d ed. Trans. W. F. Arndt and F. W. Gingrich. Revised and edited F. W. Danker. Chicago, 1979.

TAM Tituli Asiae Minoris. Vienna, 1901-.

1 Plato, Leg. 1.641 e: “All the Greeks have the idea that our city is a friend of discourse and a great discourser” (ὡς φιλόλογός τʼ ἐστὶ καὶ πολυλόγος); Plato, Lach. 183 c: “I seem sometimes to love discussions (φιλόλογος) and sometimes to hate them (μισόλογος)”; Tht. 161 a (philologos with a sophistic nuance: a lover of arguments); Diodorus Siculus 12.53.3: “The Athenians, distinguished people and lovers of discourse” (τοὺς Ἀθηναίους ὄντας εὐφυεῖς καὶ φιλολόγους). The word is particularly common in Plutarch (53 times, especially in Quaest. conv., cf. 1.10.2), where the philologoi are cultivated folk (πεπαιδευμένοι) as opposed to ἰδιῶται: “Cornelia was always surrounded by Greeks and learning” (C. Gracch. 19.2; cf. 6.4); “Cicero was fond of Greek learning” (Cic. 3.3); “the adolescent Philologos was taught in the arts and sciences” (ibid. 48.2; 49.2); Alexander “had an innate appetite for literature (φύσει φιλόλογος) and for reading” (Alex. 8.2; cf. G. Nuchelmans, “Studien über φιλόλογος, φιλολογία, und φιλολογεῖν,” Zwolle, diss. Nijmegen, 1950; H. Kuch, Φιλόλογος: Untersuchungen eines Wortes, Berlin, 1965, A. G. Kaloyeropoulo, “Epitaphe mégarienne,” in Ath. Ann. Arch., vol. 7, 1974, pp. 287–291); C. Panagopoulos, Vocabulaire, p. 227.

MAMA Monumenta Asiae Minoris Antiqua. 9 vols. Manchester-London, 1928–1988.

TAM Tituli Asiae Minoris. Vienna, 1901-.

CIL Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum. Berlin, 1862-.

ZPE Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik

2 SEG IV, 111 (cf. L. Robert, Hellenica, vol. 13, pp. 48–49; “Bulletin épigraphique,” in REG, 1938, p. 458, n. 362; 1965, p. 110, n. 180; 1974, p. 296, n. 573); XXII, 355; P.Oxy. 531, 11; IGUR, n. 736. The philologoi of P.Oxy. 2177, 40 are perhaps the teachers of the Museum of Alexandria (H. A. Musurillo, Pagan Martyrs, p. 201).

SEG Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum. Alphen, 1923-.

CIL Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum. Berlin, 1862-.

3 P.Lond. 256 a (vol. 2, p. 99, AD 15). P.Oxy. 2190, 7; SB 1481, 33; P.Apoll. 83, 11: “to the embroiderer Philologus” (an account of receipts and disbursements).

4 MAMA VIII, 241, 298 (Iconium); at Priene: ὁ τόπος Ἀλεξάνδρου τοῦ Φιλολόγου (I.Priene 313, 32; cf. L. Robert, Noms indigènes, p. 302); at Chios (SEG XVI, 488, 6), at Termessos (TAM III, 358, husband of a freedwoman), at Paros (IG XII, 5, 161); at Thera (IG XII, 3, 339, 12; 671 a 5; 1527); cf. L. Robert, Hellenica, vol. 13, pp. 45ff.

5 Cf. the references in H. Lietzmann, An die Römer, 4 th ed., Tübingen, 1933, p. 127; but Plutarch says “there is no father who loves letters (φιλόλογος), honors, or money as he loves his children” (De frat. amor. 5). Suetonius, in Rhet. 10, includes “Atticus Philologus, son of a freedman, born at Athens.”

6 Φιλόλογον ἀρχικύνηγον πίστεως καὶ φιλοπονίας ἕνεκεν, G. E. Bean, Journeys in Northern Lycia, Vienna, 1971, n. 42; but the philologoi in Dionysius of Halicarnassus (Orat. 2.8.5) are well-read people, as opposed to the general public, hence “inquiring minds” (Plutarch, Quaest. conv. 5.1.1), the learned (6.4.1), always wanting to learn more (6.8.3).

S J. Strong. Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Reprint. Peabody, n.d.

TDNT G. Kittel and G. Friedrich, eds. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. Trans. G. W. Bromiley. 10 vols. Grand Rapids, 1964–1976.

EDNT H. Balz and G. Schneider, eds. Exegetical Dictionary of the New Testament. Grand Rapids, 1990–1993.

NIDNTT Colin Brown, ed. The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology. Grand Rapids, 1986.

MM J. H. Moulton and G. Milligan. The Vocabulary of the Greek Testament Illustrated from the Papyri and Other Non-literary Sources. 2 vols. London, 1914–30. Reprint. Grand Rapids, 1985.

L&N J. P. Louw and E. A. Nida, eds. Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament: Based on Semantic Domains. 2 d ed. New York, 1989.

BAGD W. Bauer. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. 2 d ed. Trans. W. F. Arndt and F. W. Gingrich. Revised and edited F. W. Danker. Chicago, 1979.

S J. Strong. Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Reprint. Peabody, n.d.

TDNT G. Kittel and G. Friedrich, eds. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. Trans. G. W. Bromiley. 10 vols. Grand Rapids, 1964–1976.

EDNT H. Balz and G. Schneider, eds. Exegetical Dictionary of the New Testament. Grand Rapids, 1990–1993.

NIDNTT Colin Brown, ed. The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology. Grand Rapids, 1986.

MM J. H. Moulton and G. Milligan. The Vocabulary of the Greek Testament Illustrated from the Papyri and Other Non-literary Sources. 2 vols. London, 1914–30. Reprint. Grand Rapids, 1985.

L&N J. P. Louw and E. A. Nida, eds. Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament: Based on Semantic Domains. 2 d ed. New York, 1989.

BAGD W. Bauer. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. 2 d ed. Trans. W. F. Arndt and F. W. Gingrich. Revised and edited F. W. Danker. Chicago, 1979.

1 Matt 25:35; cf. J. R. Michaels, “Apostolic Hardships and Righteous Gentiles: A Study of Matthew XXV, 31–46,” in JBL, 1965, pp. 27–37; J. Winandy, “La Scène du Jugement dernier (Mt. XXV, 31–46),” in ScEccl, 1966, pp. 169–186; L. Cope, “Mt. XXV, 31–46 Reinterpreted,” in NovT, 1969, pp. 32–44; J. Mánek, “Mit wem identifiziert sich Jesus? Eine exegetische Rekonstruktion ad Mt. XXV, 31–46,” in Christ and Spirit in the N.T. (in honor of C. F. D. Moule), Cambridge, 1973, pp. 15–25.

2 Matt 10:11; Acts 16:15; 21:7, 17; 18:14; Phlm 22; Titus 3:13; 3 John 5–8; 1 Clem. 1.2: τὸ μεγαλοπρεπὲς τῆς φιλοξενίας ὑμῶν ἦθος; cf. 10.7; 11.1; 12.1; P.Oxy. 2603, 34–35: “If possible, do not hesitate to write to the other communities concerning the travelers so that they may be welcomed in each place (ὅπως προσδέξωνται κατὰ τόπον) as is meet (ὡς καθήκει)” (PSI 1041, 12); Studia Pontica, vol. 3, n. 20, 16. A. Harnack, Die Mission und Ausbreitung des Christentums, 10th ed., Leipzig, 1924, pp. 200ff. = ET The Mission and Expansion of Christianity in the First Three Centuries, trans. J. Moffatt, New York, 1908, vol. 1, pp. 347ff. D. W. Riddle, “Early Christian Hospitality: A Factor in the Gospel Transmission,” in JBL, 1938, pp. 141–154; H. Rusche, Gastfreundschaft in der Verkündigung des Neuen Testaments, Münster, 1958; J. A. Grassi, “Emmaus Revisited,” in CBQ, 1964, pp. 463–467; M. Landfester, “Philos,” pp. 112, 120, 152; C. Spicq, Théologie morale, vol. 2, pp. 809ff. In the second century, Bishop Melito of Sardis wrote a book On Hospitality (Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. 4.26.2). St. Ambrose notes: “Good hospitality earns no small reward; not only do we gain peace for our hosts, but if they are covered with the light dust of offenses, receiving apostolic preachers removes these” (In Luc. 6.66); cf. P. Miquel, “Hospitalité,” in Dict. spir., vol. 7, 808ff.

3 The first meaning of the verb ἀγαπάω is a welcoming love, which is manifested toward guests who are honored and given first-class treatment (C. Spicq, Agapè: Prolégomènes, pp. 38, 52, 66, 82, 120); cf. H. I. Kakride, Notion de l’amitié, pp. 41, 91ff.; V. T. Avery, “Homeric Hospitality in Alcaeus and Horace,” in CP, 1964, pp. 107–108.—On the pericope Rom 12:9–21, cf. C. Spicq, Agapè, vol. 2, pp. 142ff. E. Käsemann, “Gottesdienst im alltag der Welt (Röm 12),” in Judentum, Urchristentum, Kirche, (Festschrift J. Jeremias), Berlin, 1960, pp. 165–161; C. H. Talbert, “Tradition and Redaction in Rom 12:9–12,” in NTS, vol. 16, 1969, pp. 83–93.

Šabb Šabbat

4 Diodorus Siculus 13.83; Athenaeus 1.5.4; Valerius Maximus 4.8.

5 Polybius 4.20; Diodorus Siculus 13.83; Heraclides Ponticus, frag. 3, 6: φιλανθρωπία τοῖς ξένοις.

6 Dittenberger, Or. 416, 5; Plutarch, C. Gracch. 19.2: “Cornelia had many friends and a good table for welcoming them” (καὶ διὰ φιλοξενίαν εὐτράπεζος, following the French translation of R. Flacelière); cf. the inscriptions gathered by L. Robert, Etudes épigraphiques, p. 142. On ξενικὴ φιλία, cf. Aristotle, Eth. Nic. 8.1.1155a20–22 (A. J. Voelke, Les Rapports avec autrui dans la philosophie grecque, pp. 52ff.); Philo, Moses 1.35ff.; Epictetus 1.28.23; 3.11.4. A Corinthian is called Ξενόφιλος, “friend of strangers” (I.Rhamn., n. XI, 24; cf. XIV, 2). Φιλόξενος is rather common as a proper name (cf. REG, 1934, p. 224; 1936, p. 361; 1960, p. 186, n. 318; 1963, p. 276, n. 263; 1964, p. 247, n. 572; L. Robert, Noms indigènes, p. 432, n. 4; L. Robert, Stèles funéraires, Paris, 1964, n. 160). The city of Delphi honors the rhetor Herodes Atticus, φιλίας καὶ φιλοξενίας ἕνεκα (Dittenberger, Syl. 859 a).

B. Latyschev, B. Latyschev. Inscriptiones Antiquae Orae Septentrionalis Ponti Euxini Graecae et Latinae. 2. Ed. 2 vols. Hildesheim, 1965.

Inscriptiones Antiquae B. Latyschev. Inscriptiones Antiquae Orae Septentrionalis Ponti Euxini Graecae et Latinae. 2. Ed. 2 vols. Hildesheim, 1965.

Dittenberger, Sylloge Inscriptionum Graecarum. Ed. W. Dittenberger. 4 vols. 3. Ed. Leipzig, 1915. Reprint Hildesheim-New York, 1982.

Syl Sylloge Inscriptionum Graecarum. Ed. W. Dittenberger. 4 vols. 3. Ed. Leipzig, 1915. Reprint Hildesheim-New York, 1982.

7 F. Durrbach, Choix, n. 92, 20ff.

8 SEG XVIII, 143, 49ff.; cf. lines 28–29, 75ff. Cimon, “the most hospitable of the Greeks” (Plutarch, Cim. 10.4), had a meal prepared at his home every day for a large number of persons. All the poor were welcomed (10.1). He surpassed the ancient hospitality and beneficence of the Athenians (φιλοξενίαν καὶ φιλανθρωπίαν, 10.6). On Greek hospitality, cf. Heliodorus, Aeth. 2.22.1–3; A. Aymard, “Les Etrangers dans les cités grecques,” in L’Etranger (Recueils de la Société J. Bodin, IX, 1), Brussels, 1958, pp. 125ff. C. Préaux, “Les Etrangers à l’époque hellénistique,” ibid., pp. 143ff. P. Gauthier, Symbola, pp. 19ff. et passim.

9 Diodorus Siculus 5.34: “The Celtiberians were humane and benevolent toward guests. The were eager to offer their homes to strangers, vying for the honor of welcoming them and regarding as a person beloved of the gods the one whom the traveler chose as his host.”

T. Job Testament of Job

ʾAbot R. Nat. ʾAbot de Rabbi Nathan

Str-B [H. L. Strack and] P. Billerbeck. Kommentar zum Neuen Testament aus Talmud und Midrasch. 6 vols. in 7. Munich, 1922–1961.

10 Abraham’s hospitality is mentioned by Philo, Abraham 107–118; Josephus, Ant. 1.196; 1 Clem. 10.7; T. Abr. A 17: “hospitality unbounded, like the sea.” Often represented by Byzantine painters, it is invoked in Christian inscriptions: “Just as Abraham showed hospitality to the angels, Se … built.…” (IGLS 1963).

11 Apoc. Paul 27; H. Chadwick, “Justification by Faith and Hospitality,” in SP, vol. 4, Berlin, 1961, pp. 281–285.

12 Rom 16:1–2. On the requirements for lodging, cf. IGLS 1998, 11ff. Edict of Germanicus: “Having learned that because I was coming there were requisitions of boats and beasts, and that homes were forcibly taken over to provide lodging for us, and that private persons were harassed.…” (SB 3924 = Sel.Pap. II, 211.). N. Lewis, “Domitian’s Order on Requisitioned Transport and Lodgings,” in RIDA, 1968, pp. 135–142; D. Gorce, Les Voyages, l’hospitalité et le port des lettres dans le monde chrétien des IVe et Ve siècles, Paris, 1925; E. Wipszycka, Les Ressources et les activités économiques des églises en Egypt, du IVe au VIIIe siècle, Brussels, 1972, pp. 116ff.

Did. Didache

Herm. Hermas, Mandate(s)

Man. Hermas, Mandate(s)

13 P.Petr. II, 12 (cf. N. Hohlwein, Le Stratège du nome, p. 128); G. E. Bean, T. B. Mitford, Cilicia, n. 79: ἀφειδῶς δόντα καὶ διαδόματα καὶ ἐστιάσαντα πολείτας καὶ ξένους (cf. the editors’ note, p. 99).

14 Cf. the dedication θεᾷ μεγίστῃ Ἰσερμοῦθι φιλοξένῳ Ἰσίδωρος γλύπτης ἐποίει καὶ ἀνέθηκεν ἐπʼ ἀγαθῷ (SEG VIII, 538 = SB 8129).

15 Μαιτὰ φιλοξενίας μακροθυμίας πεπληρωμαίνη πνεύματος ἁγίου (P.Lond. 1917, 4 = H. I. Bell, Jews and Christians in Egypt, p. 81). Cf. G. Husson, “L’Hospitalité dans les papyrus byzantins,” in Proceedings XIII, pp. 169–177.

S J. Strong. Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Reprint. Peabody, n.d.

BAGD W. Bauer. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. 2 d ed. Trans. W. F. Arndt and F. W. Gingrich. Revised and edited F. W. Danker. Chicago, 1979.

1 Cf. F. Cumont, L’Egypte des astrologues, pp. 34ff.; E. Bickerman, Institutions des Séleucides, pp. 40ff.; K. C. Atkinson, “Some Observations on Ptolemaic Ranks and Titles,” in Aeg, 1952, pp. 204–214; C. Spicq, Agapè: Prolégomènes, pp. 165ff.; C. de Witt, “Enquête sur le titre śmr-pr,” in ChrEg, 1956, pp. 89–104; H. Donner, “Der ‘Freund des Königs,’ ” in ZAW, 1961, pp. 269–277; L. Mooren, “Über die ptolemäischen Hofrangtitel,” in Antidorum W. Peremans, Louvain, 1968, pp. 161–180. The references are given by W. Peremans, “Sur la titulature aulique en Egypte au IIe et Ier siècle avant J.-C.,” in Symbolae ad Jus et Historiam Antiquitatis Pertinentes (Symbolae von Oven), Leiden, 1946, 129–159; idem, Prosop.Ptol., vol. 6, pp. 21ff., 85; M. Holleaux, Etudes d’épigraphie, vol. 3, pp. 220–225; L. Mooren, The Aulic Titulature in Ptolemaic Egypt: Introduction and Prosopography, Brussels, 1975, pp. 52ff., 173ff., 225ff. A title of the stratēgoi (cf. G. Mussies, in Pap.Lugd.Bat. XIV, pp. 13–46) and epistratēgoi (J. David Thomas, The Epistrategos in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt, Opladen, 1975, pp. 43ff.).

2 L. Friedländer, Mœurs romaines du règne d’Auguste, Paris, 1885, vol. 1, pp. 128ff.; F. Cumont, Les Religions orientales dans le paganisme romain, pp. 127, 273, n. 6. M. Lemosse, Le Régime des relations internationales dans le haut-empire romain, Paris, 1967, pp. 44, 67, 75, 87, 93.

3 1 Macc 6:14–15: “He gave him his crown, his robe, and his ring” (cf. 6:28; 7:8; 10:19–20); Esth 6:9—“Let the garment be given to one of the friends of the king”; cf. 1:3; 2:18. A civil officer in Solomon’s court was “king’s friend”; 1 Kgs 4:5; cf. T. N. D. Mettinger, Solomonic State Officials, Lund, 1971, pp. 63–69; M. Paeslack, in Theologia Viatorum V, (Festschrift Albertz), 1954, pp. 92–93.

4 Ep. Aristides 125: “giving him the most useful advice with absolute frankness”; P.Oxy. 3019, 7; cf. I.Delos 1532, 4; 1535, 5; 1544–1548; 1571, 2; 1573, 3; 1581, 1; Dittenberger, Or. 685, 121. On the distinction between a court title and an honorific title, i.e., between the phenomenon of the φίλοι and the hierarchy created at the beginning of the second century BC, cf. L. Mooren, The Aulic Titulature in Ptolemaic Egypt; idem, La Hiérarchie de Cour ptolémaïque, Louvain, 1977.

5 1 Macc 7:8; Josephus, Ant. 13.225; Polybius 31.3.26; P.Tebt. 728, 4; 895, 11–12; UPZ 161, 2–3; 187, 1; 194, 1–2.

6 P.Dura 18, 10: τῶν πρώτων καὶ προτιμωμένων φίλων; 19, 18; 20, 3; P.Ryl. 66; Dittenberger, Syl. 651, 10; Or. 754, 2; Polybius 5.25.3: “The most illustrious of the king’s friends”; Diodorus Siculus 17.37.5; C. B. Welles, Royal Correspondence, n. 45, 3: Ἀριστόλοχον τῶν τιμωμένων φίλων. Cf. A. Momigliano, “ ‘Honorati Amici,’ ” in Athenaeum, vol. 11, 1933, pp. 136–141.

7 Πρῶτοι φίλοι, a category perhaps sometimes confused with the preceding one, 1 Macc 10:60, 65: “The king gave him the honor of enrolling him among his first friends”; 11:27; 2 Macc 8:9; P.Rein. 7, 28–29; P.Stras. 564, 14–16; P.Tebt. 778, 1; 895, 1; PSI 166–172; SB 632, 1; 9963; 9986; 10078; 10122; SEG XIII, 557, 571; XX, 208; Dittenberger, Or. 93, 3; 119; 160; 255; 256. “It is an old habit among kings and those who want to appear kingly to divide a whole population of ‘friends’ into classes; and it is a prideful thing to make a great deal of the right to cross or even approach his doorstep, and, as a supposed honor, to authorize you to stand guard near the entrance, and to step into the house in front of others.… Among us, C. Gracchus, then Livius Drusus were the first ones to establish this custom of separating their people into groups and receiving some privately, some in small groups, and others en masse. So these people had first-class friends and second-class friends, but never true friends” (Seneca, Ben. 6.34.1–2). Cf. Dio Cassius 57.11: οὐδʼ ἱππέα τῶν πρώτων εἴα; Diodorus Siculus 19.48.6: “Antigonus gave a big welcome to Xenophilus and pretended to honor him as the equal of his first friends” (ἐν τοῖς μεγίστοις τῶν φίλων). But if Diodorus calls ranking Macedonians friends in the entourage (19.91.4), and particularly royal persons (19.35.5)—which makes “friend” an official title—elsewhere the meaning is broader (cf. F. Bizière, Diodore de Sicile: Bibliothèque historique, Livre XIX, Paris, 1975, p. 156).

8 1 Macc 3:32; 2 Macc 11:12; P.Tebt. 7, 7–8; 26, 5–6; 72, 241; 700, 70; 743, 5–6; SEG XIII, 552, 553, 556, 568, 571–591; SB 4225, 1; 4321; 5219; 7410–7412; 8036, 4–5; Dittenberger, Or. 259. To this category was assimilated the τροφεύς, “tutor” or “foster father,” raised with the king, 1 Macc 1:6; SB 1568, 1; Dittenberger, Or. 148; 256. J. A. Letronne, Inscriptions, pp. 350ff.

SEG Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum. Alphen, 1923-.

Flacc. Against Flaccus (In Flaccum)

P.Oxy. The Oxyrhynchus Papyri. 51 vols. London, 1898–1984.

9 SB 624; 5827; 7270; BGU 1190; E. Bernand, Fayoum, pp. 49ff., 53ff.

10 John 19:12 (cf. C. Spicq, Agapè, vol. 3, pp. 239ff.; Stählin, “φίλος,” in TDNT, vol. 9, pp. 166–167). On the historicity of this account, cf. M. Dibelius, “Das historische Problem der Leidensgeschichte,” in Botschaft und Geschichte, Tübingen, 1953, vol. 1, pp. 248–257; “Herodes und Pilatus,” ibid., pp. 278–292; J. Blank, “Die Verhandlung vor Pilatus, Joh. XVIII, 28–XIX, 16 im Lichte johanneischer Theologie,” in BZ, 1959, pp. 60–81; J. Blinzler, Le Procès de Jésus, pp. 286, n. 13ff., 378ff; ET = Trial of Jesus.

11 But in this case, the wording would more likely be φιλόκαισαρ or φιλοσέβαστος, cf. IGLS 2759, 2760.

12 Suetonius, Tit. 7.2; Pliny, Pan. 84; Josephus, Ant. 12.298; cf. A. Deissmann, Light, p. 378; E. Bammel, “Φίλος τοῦ Καίσαρος,” in TLZ, 1952, pp. 205–210.

13 M. J. Ollivier, “Ponce Pilate et les Pontii,” in RB, 1896, pp. 247–254; 594–500; P. L. Maier, Pilatus: Sein Leben und sine Zeit, Wuppertal-Vohwinkel, 1970; R. E. Brown, John, vol. 2, pp. 847, 879.

14 Cf. T. P. Wiseman, “The Definition of ‘Eques Romanus’ in the Late Republic and Early Empire,” in Historia, 1970, pp. 67–83.

15 Without any formal nomination and therefore without the issuing of a certificate, elevation to the rank of philos—which was normal for senators—was common from the time of Augustus for legates and prefects, as a reward for their loyal service.

16 Cf. Epictetus 4.1.45–48: “the evil that is injurious and must be fled … is not being Caesar’s friend.” An offending slave only risks a lashing, but losing Caesar’s friendship can mean beheading.

S J. Strong. Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Reprint. Peabody, n.d.

EDNT H. Balz and G. Schneider, eds. Exegetical Dictionary of the New Testament. Grand Rapids, 1990–1993.

NIDNTT Colin Brown, ed. The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology. Grand Rapids, 1986.

MM J. H. Moulton and G. Milligan. The Vocabulary of the Greek Testament Illustrated from the Papyri and Other Non-literary Sources. 2 vols. London, 1914–30. Reprint. Grand Rapids, 1985.

L&N J. P. Louw and E. A. Nida, eds. Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament: Based on Semantic Domains. 2 d ed. New York, 1989.

BAGD W. Bauer. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. 2 d ed. Trans. W. F. Arndt and F. W. Gingrich. Revised and edited F. W. Danker. Chicago, 1979.

ND G. H. R. Horsley and Stephen Llewelyn, eds. New Documents Illustrating Early Christianity. North Ryde, N.S.W. 6 vols. 1981–.

Studia Pontica F. Cumont. Studia Pontica. Brussels, n.d.

1 On στοργή in the inscriptions of the first-second century, cf. GVI, n. 946, 1015, 1079, 1112, 1156, 1263, 1265, 1419, 1442, 1737, 1869, 1919, 1975, 2002, 2011. Diodorus Siculus 17.65.3: the devotion of Alexander’s officer’s to him; cf. 17.114.1.

2 TAM II, 243: φιλοστόργῳ ἀδελφῷ: IG XII, Suppl. 29: ἐκτροφῆς ἕνεκεν καὶ φιλοστοργίας τῆς ἑαυτῶν. Cf. C. Spicq, Agapè: Prolégomènes, pp. 4, n. 2; 5, n. 2; 12, n. 7; 26, n. 5; 27, n. 2; 61, n. 3. Idem, “Φιλόστοργος,” in RB, 1955, pp. 497–510. On philostorgia, brotherly love, φιλοστοργότατον ἀδελφόν (E. Breccia, Iscrizioni, n. 154; cf. 135); cf. an inscription at Pisidia: τὸν δὲ ἀνδριάντα ἀνέστησαν Νεωνιανὴ Νανηρὶς ἡ μήτηρ καὶ Φλογιανὴ Ἀννιανὴ ἡ ἀδελφὴ φιλοστοργίας καὶ μνήμης χάριν (SEG II, 713, 4–6); at Saïda, a tomb holds the body of Heraclea, a dear friend or own sister of the “old mother,” γνωθὴ θʼ Ἡεράκλεια φιλοστόργοιο τεκούσης (B. Haussoullier, H. Ingholt, “Inscription grecques de Syrie,” in Syria, 1924, pp. 338–340). A father’s affection for his children, cf. the tomb inscription τῷ υἱῷ φιλοστοργίας ἕννεκεν (C. Naour, “Inscription et relief de Kibyratide et de Cabalide,” in ZPE, vol. 22, 1976, pp. 126 and 128); between spouses, cf. the στοργὴ βεβαία of an inscription of Nicomedia published by S. Sahin, ibid., XVIII, 1975, p. 42, n. 125; cf. XXI, 1976, p. 189.

3 With mares, the maternal (φιλόστοργος) affection develops naturally (Aristotle, HA 9.4.611a12). A cruel beast, ἀστόργου θηρός (GVI, n. 1078, 4). Little ones must not be separated from their mother, especially while nursing (διά τινα φυσικὴν μητέρων πρὸς ἔγγονα φιλοστοργίαν, Philo, Virtues 128). Plutarch wrote a little treatise “On the Love (φιλοστοργία) of Offspring,” in which he observes the affection of male and female, especially the latter, toward their young (De am. prol. 2). He insists that this sentiment comes from nature (3–5).

4 Abraham 91, 168, 198; Virtues 192; Moses 1.150; Spec. Laws 2.240; 3.153, 157; To Gaius 36; Frag. 202 on Gen 27:12–13 (ed. N. Ralph, p. 230); cf. Josephus, Ant. 4.135; 7.252; 8.193; Epictetus 1.11; 3.17.4; 3.24.58ff. Plutarch (De frat. amor. 4) uses philostorgos to describe old men who are “sensitive” to the way their dog or horse is treated. On the manifestations of this affection, cf. C. Panagopoulos, Vocabulaire, p. 214.

5 Ἡ μήτηρ ὡς ἐπὶ παιδί, καὶ φύσει φιλόστοργος, P.Oxy. 1381, 104. In his will, Petosorapis asks his sister to take responsibility for his younger brother Epinicos and be a mother to him (εἰς αὐτὸν μητρικῇ φιλοστοργίᾳ, P.Oxy. 495, 12; P.Mich. 148, col. II, 9); GVI, 956, 3: φιλοστόργου μητρός; M. Dunand, in RB, 1932, p. 579: φιλοστόργῳ μητρί. “There is a foolproof way of knowing: the mother’s instinct; from the first meeting, she feels a warm affection (philostorgia) for her child” (Heliodorus, Aeth. 10.24.8). The earth is the “common hearth of gods and humans, and we must all bow before her as before a land that nourishes us and celebrate her and cherish her (ὑμνεῖν καὶ φιλοστοργεῖν) as the one who gave birth to us” (Theophrastus, in Porphyry, Abst. 2.32, p. 162, 6); “Apelles and Metrothemis, children of Cleanactides [raised this monument toj their nurse Meliteia, [daughter] of Lysanias, because of the nurture [that she gave them] and her tender affection for them” (ἐκτροφῆς ἕνεκεν καὶ φιλοστοργίας τῆς ἑαυτῶν, CIG 6850 b). Apollonis, queen of Pergamum: διεφύλαξε τὴν εὔνοιαν καὶ φιλοστοργίαν μέχρι τῆς τοῦ βίου καταστρογῆς (Polybius 22.20; cf. I.Perg. 169). Stratonice raised with affection and magnificence (ἔθρεψε φιλοστόργως καὶ μεγαλοπρεπῶς) the children that her husband had with a slave (Plutarch, Mulier. virt. 21); “friendship (φιλίας), parental love (φιλοστοργίας), and philanthropy … the link between them is indissoluble” (De virt. mor. 12); “Is philostorgia for children natural to humans?” (Quaest. conv. 2.1.13; Agis 17.4). In the aretology of Cumae, Isis presents herself: Ἐγὼ στέργεσθαι γυναῖκας ὑπὸ ἀνδρῶν ἠνάγκασα (line 27, ed. Y. Grandjean, Arétalogie d’Isis, p. 123); L. Robert, Documents, pp. 81; 84 n. 1; idem, Hellenica, vol. 13, p. 38.

6 Ῥηιγίνῃ γυναικὶ ἁγνοτάτῃ καὶ φιλοστόργῳ (IGUR, vol. 2, n. 752); IG X, 2, n. 608; MAMA I, 117; IV, 250; VIII, 235; I.Lind. 456 b 6; IGLS 1364, 6; SEG XIX, 840: γυναικὶ ἰδίᾳ φιλοστοργίης ἕνεκεν; G. Pfohl, Inschriften der Griechen, Darmstadt, 1972, pp. 171ff.; J. and L. Robert, “Bulletin épigraphique,” in REG, 1963, p. 148, n. 134; Hellenica, vol. 7, pp. 9–10; edict of Eriza (Dittenberger, Or. 224, 16; cf. 307–308); G. Kaibel, Epigrammata, n. 44, 2–3; 244, 6; Ps.-Plutarch, Cons. ad Apoll. 9: “the poet Antimachus loved his wife tenderly” (φιλστόργως); cf. Stobaeus, Flor. 24: Γυναῖκα δὲ τὴν κατὰ νόμους ἕσκατος στεργέτω καὶ ἐκ ταύτης τεκνοποιείσθω (vol. 4, p. 154,10).

7 Τὸν φιλοστοργότατον ἄνδρα. The two wives of the general Ceteus loved him tenderly (Diodorus Siculus 19.33.1–2). Πριμιτείβῳ γλυκυτάτῳ καὶ φιλοστόργῳ … πατήρ (IGUR, II, 2, n. 914). φιλοστοργίας ἕνεκεν recurs constantly in the tomb inscriptions, TAM II, 92, 93, 105, 148; SEG XX, 54, 8, 200, 7. F. K. Dörner, Bericht über eine Reise in Bithynien, Vienna, 1952, n. X, 30. The wife of the silversmith Canopys “bore witness to him for three years of a pious affection” (στοργή, E. Bernand, Inscriptions métriques, n. 19); SEG II, 712, 7; C. B. Welles, Royal Correspondence, n. 67, 2–3; cf. n. 35; G. Kaibel, Epigrammata 189, 1; 409, 6. ZPE, vol. 29, 1978, pp. 98, 104.

8 P.Tebt. 408, 7: παρακαλῶ σε περὶ υἱῶν μου τῇ φιλοστοργίᾳ (in AD 3); MAMA I, 288, 319; VIII, 247; SEG XIV, 803; SB 10652 c 2: Eudaimonis to Apollonius τῷ φιλοστοργοτάτῳ υἱῷ; I.Car. 175 b; GVI, 1950, 7; B. Latyschev, Inscriptiones Antiquae, I, 357, 6; 362, 6; 364, 7, 15; IV, 71, 6; L. Robert, Opera Minora Selecta, vol. 1, p. 311, n. 2; I. Kajanto, A Study of the Greek Epitaphs of Rome, Helsinki, 1963, pp. 29, 33.

9 Τὴν ἀγαθὴν στοργὴν πρὸς φίλιον πατέρα, F. K. Dörner, Bericht über eine Reise in Bithynien, XXII, 16; Dittenberger, Or. 229, 6; 331, 46; G. Kaibel, Epigrammata 151, 15; I.Lind. 465 d 5; I.Car. 175 b, c; I.Side 121 b 6; SEG XIV, 775, 3; H. W. Pleket, Epigraphica, vol. 2, n. 35, 5: πρὸς τοὺς γονεῖς φιλοστοργίας, cf. MAMA IV, 166; VIII, 392; C. Naour, “Inscription de Lycie,” in ZPE, vol. 24, 1977, p. 276; J. and L. Robert, “Bulletin épigraphique,” in REG, 1958, p. 325, n. 476: τὸν ἀγαθὸν καὶ φιλοστοργότατον πατέρα.

10 I.Lind. 300 c 9; 455, 10; 458, 10; 465 e 4; f 13; g 3; MAMA VIII, 367, 375; ZPE, vol. 8, 1971, p. 35; I.Sinur., n. 9, 36; cf. 14, 6; 15, 10; 38, 2.

SEG Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum. Alphen, 1923-.

11 G. E. Bean, Journeys in Northern Lycia, n. 39. In wills, slaves are often freed because of their devotion, P.Oxy. 494, 6; P.Oslo 129, 15; P.Grenf. III, 71, 12; Chrest.Mitt., n. 361, 16; in 354, a Christian freed his slaves “in gratitude for the goodwill that you have always shown toward me, your affection, and your service” (καὶ ἀνθʼ ὧν ἐνεδείξασθε μοὶ κατὰ χρόνον εὐνοίας καὶ στοργῆς ἔτι τε καὶ ὑπηρεσίας, Delphi, n. 124, cited by P. Foucart, Mémoire sur l’affranchissement des esclaves, Paris, 1857, pp. 45–46).

12 G. E. Bean, T. B. Mitford, Cilicia, n. 1, 10–14.

13 P.Mich. 341, 9: κατʼ εὔνοιαν καὶ φιλοστρονγείαν (sic) τοῦ Διδύμου πρὸς τὴν θυγατέραν Ἡερακλέαν; PSI 904; P.Stras. 284, 13; P.Oxy. 492, 5; SB 8035 a 4.

14 P.Mert. 12, 12: εἰ μὴ τὰ ἴσα σοι παρασχεῖν, βραχεία τινὰ παρέξομαι τῇ εἰς ἐμὲ φιλοστοργίᾳ.

15 The pairing φιλοστοργία-εὔνοια is constant, cf. Stud.Pal. XX, 35, 9: εὐνοίας καὶ φιλοστοργίας ἕνεκα; SB 5294, 9; Josephus, Ant. 4.134; Chrest.Mitt., n. 361, 9; Polybius 22.20.3; Vettius Valens (ed. W. Kroll), p. 76, 27; SEG VII, 382, 11: εὐνοίας καὶ στοργῆς χάριν.

16 Παρακαλῶ σε περὶ υἱῶν μου τῇ φιλοστοργίᾳ τῶν περὶ Σωτήριχον κτλ., P.Tebt. 408, 7; cf. P.Flor. 338, 10: καὶ νῦν τάχα ἡ σὴ σπουδὴ καὶ φιλοστοργεία κατανεικήσῃ τὴν ἐμὴν ἀκαιρείαν; P.Ant. 100, 2.

17 Μετὰ πάσης εὐνοίας καὶ φιλοστοργίας, I.Perg., 160, B, 19; cf. Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175–164), ποιησάμενοι πρὸς ἀλλήλους μετὰ πάσης εὐνοίας καὶ φιλοστοργίας (Dittenberger, Or. 248, 21). Letter of Antiochus VIII Grypus (125–96), τὴν πρὸς αὐτὸν εὔνοιαν μέχρι τέλους συντηρήσαντας, ἐμμείναντας δὲ τῇ πρὸς ἡμᾶς φιλοστοργίᾳ (ibid. 257, 7).

I.Ilium Die Inschriften von Ilion. Ed. P. Frisch. Bonn, 1975.

18 Ὅπως εἰδῆτε ὡς ἔχομεν φιλοστοργίας πρὸς αὐτόν, I.Perg. 248, 43 (=Dittenberger, Or. 331). Philodemus of Gadara, Hom., frag. V b 22 (ed. Olivier, p. 8).

Dittenberger, Or. Orientis Graeci Inscriptiones Selectae. Ed. W. Dittenberger. 2 vols. Leipzig, 1903–1905. Reprint Hildesheim-New York, 1970.

19 Τὰς εἰς τὰν πόλιν ἁμῶν εὐνοίας τε καὶ φιλοστοργίας τὰν μεγίσταν ἀπόδειξιν διὰ πάντων ποιούμενος, IG Vol., 1, 1145, 33 (P. Foucart, “Inscription de Gythion,” in REG, 1909, pp. 405–409); cf. Dittenberger, Or. 231, 16–18; 256, 8; I.Delos 1517, 11 (F. Durrbach, Choix, pp. 154–155); SEG IV, 418 B 10.

20 Διὰ τὴν πρὸς τὴν πατρίδα φιλόστοργον εὔνοιαν (A. H. Jones, “Inscriptions from Jerash,” in JRS, 1928, pp. 153–156). Decree of the city of Olymos in Caria: διακείμενος φιλοστόργως πρὸς ἕκαστον τῶν πολιτῶν (Dittenberger, Or. 248, 21); Polybius 31.25.1: φιλοστοργία πρὸς ἀλλήλους. F. G. Maier, Griechische Mauerbauinschriften, Heidelberg, 1959, n. XLIV, 8; L. Robert, Opera Minora Selecta, vol. 1, p. 311.

21 P.Oxy. 1380, 12: ἐκ τῂ Καρήνῃ φιλόστοργον; cf. line 131: κόσμον θηλειῶν καὶ φιλόστοργον; Dittenberger, Syl. 1267, 23; cf. SB 591. St. John Chrysostom calls God πατὴρ φιλόστοργος (A. Wenger, Jean Chrysostome: Huit catéchèses baptismales, Paris, 1957, pp. 135, 142, 144, 150, 182, 184, 197). On philostorgia to describe the feelings of a person or a city toward a king, cf. the references in M. Holleaux, Etudes d’épigraphie, vol. 3, pp. 94ff.

22 L. Robert, Etudes anatoliennes, p. 352 b and c, p. 366.

Dittenberger, Or. Orientis Graeci Inscriptiones Selectae. Ed. W. Dittenberger. 2 vols. Leipzig, 1903–1905. Reprint Hildesheim-New York, 1970.

TAM Tituli Asiae Minoris. Vienna, 1901-.

23 Cf. “love of life,” πρὸς τὸ ζῆν φιλοστοργίαν (2 Macc 6:20). In his treatise On Marriage, Antipater of Tarsus contrasts conjugal and paternal love to friendship and other relations (φιλίαι ἢ φιλοστοργίαι); Stobaeus, Ecl. 67.22.25, vol. 4, p. 508. Likewise, Julius Pollux (Onom. 5.20.114) gives as synonyms of φίλος· εὔνους, οἰκεῖος, ἐπιτήδειος, ἑταῖρος and adds ὁ γὰρ φιλόστοργος ἕτερόν τι. Later on, when listing synonyms for φιλόστοργος, he includes φιλότεκνος, ανδ φιλόμουσος (6.37.167).

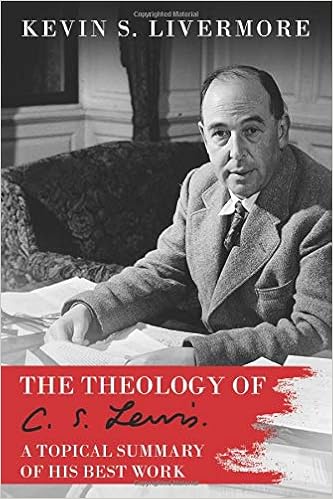

Ceslas Spicq and James D. Ernest, Theological Lexicon of the New Testament (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1994), 448–465.

![]()

Shop for Theological Lexicon of the New Testament, TLNT, Ceslas Spicq Translated by James D. Ernest, (Hendrickson, 1/1/1996).

Shop for Theological Lexicon of the New Testament, TLNT, Ceslas Spicq Translated by James D. Ernest, (Hendrickson, 1/1/1996).

month of October 2023 Logos Bible Software Discount code MINISTRYTHANKS GET 10% Off 50 12% Off 200 15% OFF 500

|

_

10% Offer on gourmet sweets for New Year | Use WELCOME24

_

10% Offer on gourmet sweets for New Year | Use WELCOME24 __________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Learn about the best nootropics, available from Bright Brain.

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Cram is a nootropic supplement for those who need maximum enhanced mental performance, focus, concentration, and memory in concise time frames such as exams, presentations, labs or any situation in which extreme mental performance is needed for a short-term period.

_________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Absolute Focus Is The #1 Nootropic Supplement For mental performance, learning, focus, alertness, cognitive improvement, logical reasoning, memory recall, overall energy and more.

__________________________________________________________________________

Triton PokerLLC________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Learn about the best nootropics, available from Bright Brain.

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Cram is a nootropic supplement for those who need maximum enhanced mental performance, focus, concentration, and memory in concise time frames such as exams, presentations, labs or any situation in which extreme mental performance is needed for a short-term period.

_________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Absolute Focus Is The #1 Nootropic Supplement For mental performance, learning, focus, alertness, cognitive improvement, logical reasoning, memory recall, overall energy and more.

__________________________________________________________________________

Triton PokerLLC________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

Levi's MEN'S CLOTHING ON SALE

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

Levi's MEN'S CLOTHING ON SALE

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________

Get a loan or start a bank account with Americas Christian Credit Union in Glendora California

______________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________

Get a loan or start a bank account with Americas Christian Credit Union in Glendora California

________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________

No comments:

Post a Comment