Monday, August 19, 2024

Excerpt from John MacArthur's Book Unleashing God's Word in Your Life

Default "Search This Blog" widget

Custom "Search The Blog" widget

The Most Popular Posts of All Time listed in order

-

We want to hear from interpreters, applicants and representatives to gather feedback for sig...

-

Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is...

-

Don't miss out on your chance to join us so you can hear from and ask questions to our great line-up of speakers ...

-

Plus more from TIME | Email not displaying correctly? View it in your browser. ...

-

The Pilgrim's Progress Weekly Devotional: Castle Despair. On the road to the Celestial City, Christian looks ahead and sees th...

Explanation of BDAG and Free Logos Training Videos

• |

The following website is called Indie Reader and the founder is Amy Edelman . it is an Arts & Humanities Website (the company is called Edelman Books/Media)

_

10% Offer on gourmet sweets for New Year | Use WELCOME24

_

10% Offer on gourmet sweets for New Year | Use WELCOME24The Lila Rose Podcast - - - There are 200 Episodes in this Podcast widget

Judson Cornwall YouTube Video

Human Trafficking Victims Program Introduction

She said two urls that are no longer the urls to use.

The first one, www.dhs.gov/humantrafficking automatically becomes www.dhs.gov/blue-campaign

The facebook site was the old site which does not automatically update to the following, the new facebook site is http://facebook.com/dhsbluecampaign

Click this link to search all of the DHS site for mentions of the Blue Campaign

Remarkable items

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Learn about the best nootropics, available from Bright Brain.

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Cram is a nootropic supplement for those who need maximum enhanced mental performance, focus, concentration, and memory in concise time frames such as exams, presentations, labs or any situation in which extreme mental performance is needed for a short-term period.

_________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Absolute Focus Is The #1 Nootropic Supplement For mental performance, learning, focus, alertness, cognitive improvement, logical reasoning, memory recall, overall energy and more.

__________________________________________________________________________

Triton PokerLLC________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Learn about the best nootropics, available from Bright Brain.

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Cram is a nootropic supplement for those who need maximum enhanced mental performance, focus, concentration, and memory in concise time frames such as exams, presentations, labs or any situation in which extreme mental performance is needed for a short-term period.

_________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Absolute Focus Is The #1 Nootropic Supplement For mental performance, learning, focus, alertness, cognitive improvement, logical reasoning, memory recall, overall energy and more.

__________________________________________________________________________

Triton PokerLLC________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

Levi's MEN'S CLOTHING ON SALE

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

Levi's MEN'S CLOTHING ON SALE

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

In Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church, top-selling author and Anglican bishop, N.T. Wright tackles the biblical question of what happens after we die and shows how most Christians get it wrong. We do not “go to” heaven; we are resurrected and heaven comes down to earth--a difference that makes all of the difference to how we live on earth. Following N.T. Wright’s resonant exploration of a life of faith in Simply Christian, the award-winning author whom Newsweek calls “the world’s leading New Testament scholar” takes on one of life’s most controversial topics, a matter of life, death, spirituality, and survival for everyone living in the world today. ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

| I saw it on Fastbuy Inc Buy Cheap Ukulele, Glarry Best Ukuleles for Sale - Glarry |

Survey Junkie

Bible Study Material Free Shipping On Orders of $30 Or More

(continental U.S., excludes digital products)

________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________

Affiliate marketer links:

Affiliate marketer Rick Livermore with Webmaster220 Bible Study Blog will earn a commission on the Bible Study Material you buy from

Want to buy Shawn Livermore's books on Alibris?

Want to buy Shawn Livermore's books on Amazon?

Brought to you by

Rick Livermore

also a fan of various The Fish stations all over the country

also a fan of Clap your hands - LAMB - Joel Chernoff

Psalm 47

1 Oh clap your hands, all ye peoples; Shout unto God with the voice of triumph.

2 For Jehovah Most High is terrible; He is a great King over all the earth.

3 He subdueth peoples under us, And nations under our feet.

4 He chooseth our inheritance for us, The glory of Jacob whom he loved. Selah

Biblical & Prophetic Music!

The Official Channel for Lamb & Joel Chernoff

Pioneer / Popularizer of the Messianic Jewish Music Genre. Shalom friends!

Welcome!

Throughout the years, the pioneering lyrics and sound of LAMB have provided countless hours of joyful praise and meaningful worship for followers of Yeshua around the world. Many of LAMB's classic songs have become anthems of faith in the Messianic community that are sung in congregations and homes and wherever else believers in Yeshua gather together to praise and worship their Messiah!

(Updated 2020 Edition!)

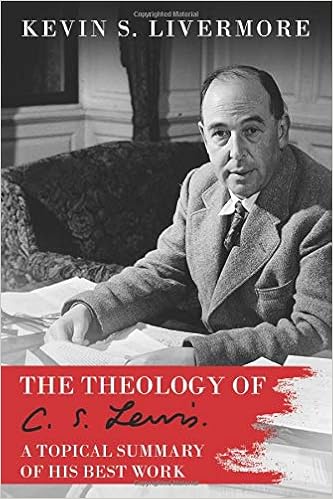

Despite his status as one of the most influential and intelligent Christian authors of the 20th century, C.S. Lewis never thought of himself as a professional theologian. While he was well-read in many types of literary genres, he did not go to Seminary to obtain a Masters in Theology and study a year of Old Testament Hebrew and New Testament Greek. He was not a Pastor who preached sermons to a congregation for many years but a raw, honest philosopher and professor of literature who wrote as well as any Christian of his time could. He had a gift for clearly articulating his perspectives on a variety of issues. Above all, he was humble, in that he had an honest evaluation of both his strengths and his weaknesses. I believe this is one of the main reasons why he is still so enjoyable to read even after all these years. In terms of his theology, Lewis himself said he was an “Anglican but not especially ‘high,’ nor especially ‘low,’ nor especially anything else.” So the theology of C.S. Lewis is not something one can immediately discover by simply perusing a certain book of his to see exactly where he stands on certain doctrinal issues; it is much more subtle and convoluted than that. But in this book, you will find his different thoughts from his many books about certain Christian doctrines and topics pieced together in an easy-to-follow format (Lewis has written nearly 60 books but none of them are on systematic theology). This book offers very clear depictions of his theology concerning subjects such as the doctrine of inspiration, original sin, human depravity, human origins, evolution, intelligent design, theodicy, love and marriage, redemption, grace, new creation, and grief, as his authentic reaction to God after his wife’s death is conveyed. The final chapters also contain all of his greatest quotes arranged and sorted by topic as well as excerpts, quotes, and summaries from most of his books in a quick, easy-to-read, bullet-point format. These last two sections are a particularly great resource to draw from as you can quickly learn about the main points Lewis conveys in his bestselling books.

__________________________________________________

______________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________

Get a loan or start a bank account with Americas Christian Credit Union in Glendora California

______________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________

Get a loan or start a bank account with Americas Christian Credit Union in Glendora California

________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________

| I saw it on ChefsTemp Best Steak Thermometer 2021: ThePocket Pro |

Sky Spills Over

2,380,500 views May 27, 2015 This song is on the album "Sovereign" From Michael W. Smith

Sky Spills Over · Michael W. Smith

Sovereign

℗ 2014 The MWS Group, under exclusive license to Sparrow Records

Released on: 2014-01-01

Producer: Christopher Stevens

Composer Lyricist: Michael W. Smith

Composer Lyricist: Christopher Stevens

Composer Lyricist: Ryan Smith

MICHAEL W SMITH Twitter Widget

List of blog posts on this blog that are Twitter Widgets

Training for Azure

Edureka Text Ads

Weekend Offer - Flat 30% OFF On Live Courses, Coupon Code - EDUREKA30

Black Friday OFFER - Flat 20% OFF On Masters Courses - Coupon Code - BLACK20

Thanks Giving Day Offer -Flat 30% OFF On All Live Courses, coupon Code - THANKS30

Weekend Offer - Flat 30% OFF On Live Courses, Coupon Code - EDUREKA30

Flat 20% OFF On All Live Courses - Coupon Code - EDUREKA20

Flat 10% OFF on Any Masters Course - Coupon Code- MASTERS10

Be a Certified Big Data Expert Master Big Data, Hadoop, Spark, Cassandra, Talend and Kafka and become an unchallenged big data expert. Know more!

Be a Certified Cloud Architect Master Cloud Computing, AWS, DevOps and become an unchallenged cloud expert. Know more!

Be a Certified DevOps Engineer Master DevOps, Python, Docker, Splunk, AWS and Linux and become an unchallenged DevOps expert. Know more!

Be a Certified Data Scientist Master Data Science, Python, Spark, Tensorflow and Tableau and become an unchallenged data science expert. Know more!

MySQL DBA Live Online Training by Edureka

MySQL DBA Online Training by Edureka Gain expertise in MySQL Workbench, MySQL Server, Data Modeling, MySQL Connector, Database Design, MySQL Command line, MySQL Functions etc.

Flat 20% OFF

Flat 15% OFF

Flat 10% OFF

Become an Expert in Big Data and Analytics . View all courses!

Big Data and Analytics Live Online Training by Edureka

Become an Expert in Cloud Computing . View all courses!

Cloud Computing Live Online Training by Edureka

Become an Expert in Business Intelligence & Visualization . View all courses!

Business Intelligence & Visualization Live Online Training by Edureka

Become an Expert in DevOps. View all courses!

DevOps Live Online Training by Edureka

Become an Expert in Programming and Web Development.View all courses!

Become an Expert in Software Testing.View all courses!

Software Testing Live Online Training by Edureka

Become an Expert in Project Management.View all courses!

Become an Expert in Mobile App Development.View all courses!

Mobile App Development Live Online Training by Edureka

Become an Expert in Finance & Marketing.View all courses!

Finance & Marketing Live Online Training by Edureka

Become an Expert in Power BI.View upcoming batches!

Power BI Live Online Training by Edureka

Become an Expert in Docker.View upcoming batches!

Docker Live Online Training by Edureka

Become an Expert in AI and Deep Learning with TensorFlow.View upcoming batches!

AI & Deep Learning with TensorFlow Live Online Training

Become an Expert in Microsoft Azure.View upcoming batches!

Microsoft Azure Live Online Training

Become an Expert in ReactJS with Redux.View upcoming batches!

ReactJS with Redux Live Online Training

Become an Expert in Blockchain.View upcoming batches!

Blockchain Live Online Training

DevOps Live Online Training by Edureka

Top PMP exam preparation online course Crack PMP exam and get the pre-requisite 35 contact hours of project management education.

Linux Live Online Training Learn Installation, User Admin, Initialization, Server Config, Shell Scrip, Kerberos, Database Config. Know More

Node.js Online Training ExpressJS,EJS,Jade,Handlebars, Template,Gulp. Work on 5 Real-life Projects using Node JS

Web Developer Live Online Training by Edureka

Web Developer Online Training Learn HTML5, CSS3, JavaScript, jQuery,Twitter Bootstrap, Social Media Plugins. Know More!

Node.js Live Online Training by Edureka

Linux Admin Live Online Training by Edureka

Become an Expert in using Spring Framework. View Upcoming Batches!

Spring Live Online Training by Edureka

Talend Online Training Learn Talend Architecture, TOS, Hive in Talend, Pig in Talend. Work on Real-life Project, Get Certified.

Talend Live Online Training by Edureka

AWS Architect Live Online Training by Edureka

Informatica Live Online Training by Edureka

Java Live Online Training by Edureka

Python Live Online Training by Edureka

Openstack Live Online Training by Edureka

AngularJS Live Online Training by Edureka

Teradata Live Online Training by Edureka

Selenium Live Online Training by Edureka

Android Live Online Training by Edureka

Kafka Live Online Training by Edureka

Splunk Live Online Training by Edureka

Data Analytics Live Online Training by Edureka

Hadoop Admin Live Online Training by Edureka

Spark Live Online Training by Edureka

Big Data and Hadoop Live Online Training by Edureka

Data Science Live Online Training by Edureka

PMP Live Online Training by Edureka

Top online course certified by Project Management Institute (PMI) Get in-depth knowledge and understanding in various Agile Tool & Techniques.

Data Science Training by Edureka Drive Business Insights from Massive Data Sets Utilizing the Power of R Programming, Hadoop, and Machine Learning.

Big Data and Hadoop - Training by Edureka Become a Hadoop Expert by mastering MapReduce, Yarn, Pig, Hive, HBase, Oozie, Flume and Sqoop while working on industry based Use-cases and Projects. Know More!

Apache Spark and Scala - Training by Edureka Learn large-scale data processing by mastering the concepts of Scala, RDD, Spark Streaming, Spark SQL, MLlib and GraphX. Know More!

Hadoop Administration - Training by Edureka Become Hadoop Administrator by Planning, Deployment, Management, Monitoring & Tuning in Hadoop Cluster. Know More!

Analytics Training with R Master Regression, Data Mining, Predictive Analytics. Know More!

Splunk Certification Training Become an expert in searching, monitoring, analyzing and visualizing machine data in Splunk. Learn Splunk and get certified.

Financial Modeling with Advanced Valuation Techniques - Training by Edureka Become an expert in financial modeling by live online training conducted by industry experts. Know More!

Apache Kafka- Training by Edureka Become an expert in high throughput publish-subscribe distributed messaging system by mastering Kafka Cluster, Producers and Consumers, Kafka API, Kafka Integration with Hadoop, Storm and Spark. Know More!

Edureka - Live Online Training

Android Development- Training by Edureka Create Android apps, integrate them with Social Media, Google drive, Google maps, SQLite, etc. while working on Android Studio. Know More!

Testing With Selenium WebDriver- Training by Edureka Master the software automation testing framework for web applications using TDD, TestNG, Sikuli, JaCoCo. Know More!

Teradata Training by Edureka Become an expert in developing Data Warehousing applications using Teradata while working on real time use cases and projects. Get trained for TEO-141 and TEO-142 certifications. Know More!

AngularJS Training by Edureka Boost your web application development skills and become an invaluable SPA (single page application) developer. Know More!

SAS Certification Training by Edureka Become a Base SAS Expert by mastering the various concepts of SAS Language while working on real-life use cases and projects. Know More!

Openstack Training by Edureka Become an OpenStack expert by mastering concepts like Nova, Glance, Keystone, Neutron, Cinder, Trove, Heat, Celiometer and other OpenStack services. Know More!

Python Training by Edureka Learn Python the Big data way with integration of Machine learning, Hadoop, Pig, Hive and Web Scraping. Know More!

Java/J2EE and SOA - Training by Edureka Get a head start into Advance Java programming and get trained for both core and advanced Java concepts along with various Java frameworks like Hibernate & Spring. Know More!

Informatica PowerCenter 9.X Developer & Admin - Training by Edureka Master ETL and data mining using Informatica PowerCenter Designer. Know More!

DevOps Training by Edureka Gain expertise in various Devops processes and tools like Puppet, Jenkins, Nagios, GIT for automating multiple steps in SDLC, Ansible, SaltStack, Chef. Know More!

AWS Architect Certification Training by Edureka Master the skills to design cloud-based applications with Amazon Web Services. Know More!

Power BI Certification Training by Edureka Master the concepts about Power BI Desktop, Power BI Embedded, Power BI Map, Power BI DAX, Power BI SSRS. Know More!

Docker Certification Training by Edureka Master the Docker Hub, Docker Compose, Docker Swarm, Dockerfile, Docker Containers, Docker Engine, Docker Images. Know More!

Microsoft Azure Certification Training by Edureka Master the concepts like Azure Ad, Azure Storage, Azure SDK, Azure Cloud Services, Azure SQL Database, Azure Web App. Know More!

Tensorflow Certification Training by Edureka Master the concepts such as SoftMax function, Autoencoder Neural Networks, Restricted Boltzmann Machine (RBM). Know More!

Data Warehousing Live Online Training by Edureka

Data Warehousing & BI Live Online Training by Edureka

LifeNews.com

Greg Laurie (Devotion) Rss Feed

Crossing Barriers from John 4:26 by Greg Laurie on Jan 6, 2025

The Discontinued New Rick Livermore Site Rss Feed

Books A Million Newsletter

|

Wow. You must be kidding me! This is a way for the blog to really begin to pay commissions!

| This email to the blog is dated 6/16/2024 but I did not read the email until today 7/30/2024 | Sun, Jun 16, 12:12 PM |    |

Consumer Cellular

NT Resources

Christian Music Videos

Daily Radio Program with Charles Stanley - In Touch Ministries

The Briefing - AlbertMohler.com

Boundaries Books

Apologetics315

The Washington Times stories: Security

Fuller Youth Institute Blog

This is from Harvard University:

YouTube Bible Gateway Basics Tutorial

Staff Picks

ICE Headline News Feed by Category - Human Smuggling/Trafficking

Crosswalk.com

Bible.org Blogs

95.9 The Fish - Jobs RSS

Bible Gateway Blog

Love Life

Strang Report

Man in the Mirror

Recent Blog Entries

Messages by Desiring God

billmounce.com - For an Informed Love of God

Search Widget: Bible Lookup for websites widget

The Rss Feed of Pastor Rick Warren

No comments:

Post a Comment